Easements

A private right of way is an easement, which is the right to use part of another's property in a particular way even though they do not own it. There are four main categories of easements (or rights), over an adjoining parcel of land. These are rights of way, rights of light and air, rights of support and rights relating to artificial waterways.

All easements have similar properties in that:

- There must be two adjoining properties; one of which has the benefit of the right, known as the dominant tenement (this is a positive easement), and one which has the burden of the right, known as the servient tenement (this is a negative easement).

- The owners of the two properties must be different from each other.

- The right must be recorded by deed and in the case of registered land, should be recorded on the Title Register for each property affected.

Express Easements

An express easement is expressed to be so by deed (Section 1(2) Law of Property Act 1925) and in the case of registered land is referred to in the A Section of the Title Register for the dominant tenement and in the C Section of the Title Register for the servient tenement.

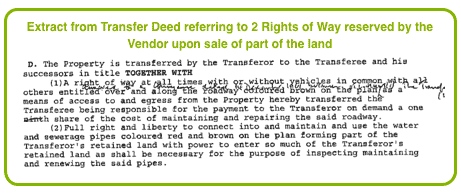

An example of an express easement is where, on the sale of part of a parcel of land the vendor agrees that the purchaser may have a right of way along his drive. This will be recorded in the transfer deed and an entry will by made by the Land Registry in the A section of the purchaser's new Title Register and in the C section of the vendor's existing Title Register.

An express easement is usually created on the sale by the vendor of part only of his property. The easement will usually be created to allow the vendor to continue to enjoy his remaining property, as where he will require a right of way over the parcel of land he has sold in order to reach his remaining property, or a right to access sewers or drains that used to be on his property, but are now within the new owner's property.

Similarly, the new purchaser may require a right of way over the vendor's retained land in order to reach the land he has purchased.

Implied Easements

Implied easements are not created by deed but are implied by law, the courts looking at what the original parties intended and how the property is being used.

An implied easement may exist where a vendor sells a parcel of land, retaining an adjoining parcel of land for himself, but where he overlooks expressly granting himself a right of way to allow him to access to his retained land.

A presumption operates that a vendor will have had ample opportunity to reserve a right of way for himself, and as he has not done so the implied right of way is more limited in scope than the express right would have been, e.g. there might be an implied right of way by foot only, rather than a vehicular right of way.

Easements of Necessity

An easement of necessity only comes into existence once the court makes an order for the same. Usually the easement is required because a property owner cannot obtain entrance to his land without crossing an adjacent parcel of land, i.e. his property is landlocked. In such circumstances application must be made to the court for the easement on the grounds that it is necessary for the enjoyment of the property. A similar right might exist where a gable wall requires repair but cannot be reached save by accessing an adjoining property.

The court will decide whether to grant the easement by deducing the intention of the original parties and whether the damage or inconvenience would be greater for the dominant or the servient tenement and make an order accordingly.

Once the need for an easement of necessity ceases to exist, e.g. because an access path is made or because a legal easement is created by deed, then the easement of necessity automatically ceases to exist.

Easements by Prior Use

It is possible to create an easement simply by having used the property in a similar way before. The court will assume that the parties intended to create it but forgot to declare the easement in the deeds.

In order for such an easement to exist it must be shown that:

- Both properties were once in the joint ownership of a person or persons.

- The properties were divided.

- That the use for which the easement is required existed before the properties were divided.

- That the easement was patently obvious, i.e. is discernible by inspection.

- The easement is reasonably necessary and will benefit the dominant tenement.

Easements by Prescription

Easements by prescription are similar to claims for adverse possession (or squatter's claims) in that they follow the use of land, without the owner's consent, openly and over a continuous period of at least 20 years (10 years for squatters). The main difference is that the use of the land is shared by more than one person. If the owner of the property acts to defend his property rights at any time before the above period has expired then the prescriptive right will cease, and any attempt to re-establish it will have to begin again.

Easements by prescription may arise either:

- Under the common law

- Under the Prescription Act 1832, or

- By lost modern grant.

The right of way claimed must be one that could have been granted in accordance with the law. For example a right of way claimed for the purpose of tipping rubbish unlawfully on land could not have been lawfully granted and cannot be acquired by prescription. On the other hand, a right to drive a vehicle over land that is a restricted byway without lawful authority is an offence, but as lawful authority could have been given then such a right is capable of being acquired by prescription.

It should be noted that prescriptive rights cannot be acquired over railway land or land owned by the British Waterways Board, by virtue of the British Transport Commission Act 1949.

Easements by Estoppel

Easements by estoppel are created by the court to prevent an inequitable outcome where the vendor has misrepresented that he would grant an easement to the purchaser but in fact did not expressly grant the same. If the purchaser bought the property and relied in good faith on the existence of such an easement as part of his decision to buy then the court will normally make an order for the easement.

For example, the purchaser may tell the vendor that he wishes to build a garage on part of the land being sold to him and the vendor may agree that he can access the garage by using a particular drive on his land. If no easement is granted by deed to effect such a right, but the purchaser has relied on the vendor's representation in consideration of purchasing the property then he would be entitled to an easement by estoppel.